Matthew RobinsonGHTC

Matthew Robinson is a policy and advocacy officer at GHTC who leads the coalition's multilateral advocacy work.

Photo: PATH/Will BoaseLast week, GHTC convened a panel of experts to dissect and discuss a proposal

for pooled funding for global health research and development (R&D). The result of many years of brainstorming and negotiating by the World Health

Organization (WHO) Consultative Expert Working Group on Research and Development (CEWG), the fund would finance neglected disease R&D at WHO’s

Special Program for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (WHO-TDR).

Photo: PATH/Will BoaseLast week, GHTC convened a panel of experts to dissect and discuss a proposal

for pooled funding for global health research and development (R&D). The result of many years of brainstorming and negotiating by the World Health

Organization (WHO) Consultative Expert Working Group on Research and Development (CEWG), the fund would finance neglected disease R&D at WHO’s

Special Program for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (WHO-TDR).

Based on the discussion, here are my five key takeaways.

1. It has been a long process and the proposal has shifted over time.

A pooled R&D fund and global health observatory are the end products of a decade-long debate rooted in the struggle to expand access to antiretroviral treatment in the early 2000s. This movement led to the Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health—which permitted member states to circumvent patents to expand access to medicine. Rachel Cohen, Regional Executive Director at Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative North America, noted, “There was a growing recognition in the early 2000s of the failure of the R&D system to deliver, particularly for diseases that really fell outside the market.” Cohen further remarked, “That really produced the political impulse to start the process.” As a result of this movement, the CEWG was established in 2010 to look at ways to finance R&D for neglected diseases. The CEWG initially proposed establishing a global treaty requiring member states to dedicate .02 percent of their gross domestic product to health R&D with 20 percent of the amount raised through the treaty going to a pooled fund for neglected diseases. Over time the challenges of a treaty became clear, and the goal shifted to the current proposal to create a voluntary fund.

2. The current proposal fulfills two distinct and separate functions—financing and coordination.

While much of the public discussion has focused on the pooled fund, there are actually two components to the proposal: the pooled fund and an R&D observatory. The observatory would serve as an online compendium of all target product profiles (TPPs) for neglected disease products in the global pipeline. Given that TPPs contain comprehensive information on product candidates, including target pricing, target markets, access considerations, and other details, the observatory would give a comprehensive picture of the gaps in the global product development pipeline. Having identified these gaps, the public health community could then convene a dialogue to determine the most pressing priorities for research. Once those priorities are identified, the pooled fund would be deployed to fund R&D for products addressing the needs identified.

3. Sufficient funding is not guaranteed, and the space is already crowded.

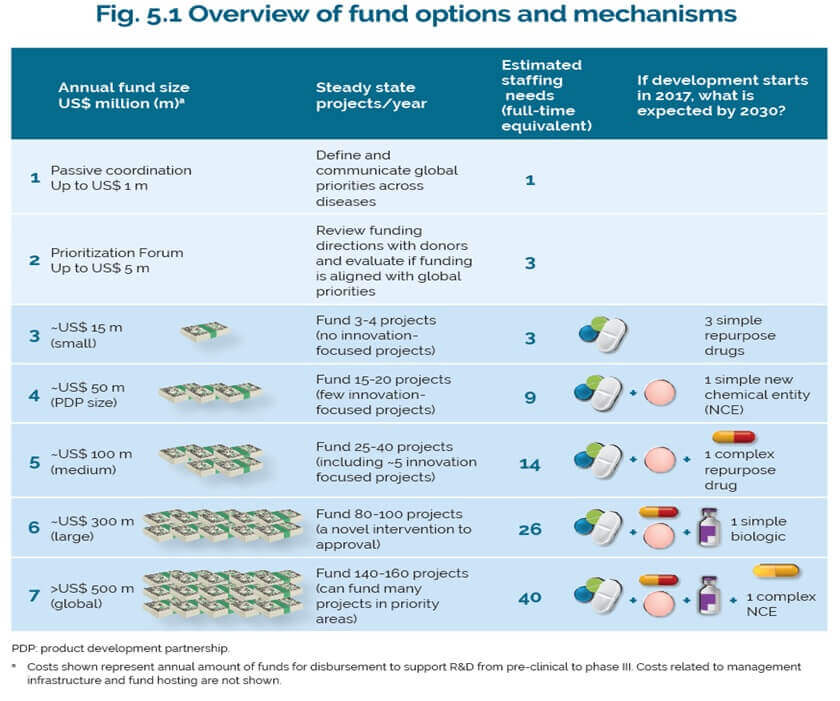

WHO-TDR has modelled a variety of scenarios on what the fund could finance. Depending on the level of resources raised, the pooled fund could support R&D projects ranging from developing a limited number of simple repurposed drugs for around US$15 million per year to developing novel biologics and new chemical entities for around $500 million per year. While the hope is that a pooled fund would attract contributions from low- and middle-income countries that might not be able to fund their own freestanding R&D programs, it is unclear how much the fund could raise even with matching funds from existing donors. Furthermore, given that all contributions are voluntary, the fund would need to actively fundraise to support its work, which requires additional staff and resources purely devoted to these activities.

According to Andrea Lucard, Executive Vice President of Medicines for Malaria Venture, concerns persist that “this actually may increase fragmentation” for R&D funding. Lucard asks further, “Are we at risk of siphoning off funds that exist from donors that are already there or donors that are close to being able to fund [existing] dynamic successful organizations?”

Credit: WHO TRD

Credit: WHO TRD

4. The necessity of fundraising risks mixing the technical with the political.

With the shift from a treaty to voluntary contributions comes growing tension between the observatory and pooled fund. The observatory must be driven by technical public health analyses such that the priorities it sets are credible, and the pooled fund must actively fundraise from individual donor nations. With fundraising comes the question of the level of influence the donor gets for its money. As we have seen in other pooled funds, the struggle between political and technical considerations is a very real problem. If the fundraising activities to support the pooled fund end up casting doubts on the observatory’s credibility, the observatory will have largely lost its ability to fill its mandate. In addition, tying the observatory to the fund runs the risk of losing the benefits of the observatory should the fund fail to raise sufficient funds and force the closure of the observatory as well through lack of funding.

5. The observatory and pooled fund are only one approach to increasing access to medicines.

While the pooled fund and observatory could potentially improve access to medicines by mobilizing more funds to directly finance R&D for neglected diseases, they would still operate within the existing overarching framework governing global health R&D. Rachel Cohen commented that the only way the pooled fund would be successful is if it is “based on a financing of R&D that disconnects, or de-links the cost of R&D from the pricing of final products.” This reflects the broader debate within the global health R&D community over exactly how to reform current policies to better promote access to medicines.

The next step in the process is an open-ended meeting on May 2-4 where WHO-TDR will formally present its proposal for the observatory and pooled fund to WHO member states, who will then decide whether to move forward with a World Health Assembly resolution. Prior to that meeting, we expect that the full report and dataset underpinning WHO-TDR’s analysis will be published on March 17th.