Breakthrough ideas are like children—they start small, they need constant nurturing, they don’t always develop according to schedule, but they change

lives forever.

In honor of Mother’s Day, GHTC is highlighting the stories of five mothers who have given birth to scientific discoveries or bold ideas that have transformed

global health.

1. Ruth Bishop (b. 1933), Discoverer of Rotavirus

- Ruth Bishop at work in her lab. Photo: Stepping Stone Pictures

As a young bacteriologist working in the 1970s, Ruth Bishop was on a quest to find the root cause of diarrheal disease—the most common illness among

children worldwide. After much research, Bishop concluded that the disease was likely not caused by a bacterial agent, but instead by a virus.

To continue her search, Bishop teamed up with two colleagues at the University of Melbourne – virologist Ian Holmes and electron microscopist Brian Ruck.

In 1973, using an electron microscope, the team uncovered a previously unidentified virus in the biopsy sample from an intestinal lining. Bishop and

her team went on to confirm presence of the virus in other samples. Their published results elicited a global response and confirmation of the virus’s

presence in samples around the globe. The virus identified by Bishop and her team would come to be named rotavirus for its wheel-like shape. Rotavirus

is the leading cause of severe diarrhea in children worldwide and affects nearly every child in their first three years of life.

Bishop and her team went on to develop a diagnostic test for the virus, and their continued research helped pave the way for the development of a rotavirus

vaccine which was introduced more than three decades after their initial discovery. Today there are two rotavirus vaccines commercially available with additional candidates in the research pipeline. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance estimates that by 2030, 2.4 million lives could be saved through rotavirus immunization.

Bishop, who is the mother of one son and is now officially retired, has watched these vaccine developments with excitement. “Rotavirus will always be around,” she said, “but we can stop it from being a killer.”

2. Rosalyn Sussman Yalow (1921-2011), Unlocked breakthrough diagnostic technique

- Rosalyn Yalow at Bronx Veterans Administration Hospital in October 1977. Photo: US Information Agency

Rosalyn Sussman Yalow knew by the age of eight that she wanted to be a scientist. Despite living in a time when few scientific opportunities were available

to women, Yalow remained undeterred in her pursuit. After completing her master’s degree and PhD in physics while working as an electrical engineer

and college instructor, Yalow decided she wanted to be a full-time researcher.

Unable to find a research position, Yalow decided to volunteer at a Columbia University radiological research laboratory. There she was introduced to the

emerging field of radiotherapy. A few years later in 1950 while working at the Bronx Veterans Affairs Hospital, Yalow would meet and begin working

with her lifelong research collaborator Solomon Berson. Together the two would develop radio-immunoassay, a technique that used radioactive isotopes

as markers to trace and measure concentrations of hormones, viruses, enzymes, and other substances in the body. Their discovery of this technique revolutionized

biological and medical research and made possible the development of diagnostic tests for infertility, hypothyroidism, and dwarfism; and screening

tests for infectious diseases such as hepatitis and HIV and AIDS in blood donations.

In 1977 Yalow became the second woman to earn a Nobel Prize in medicine.

A mother of two children, Yalow advocated for the advancement of women in sciences. In her Nobel Prize banquet speech, she said of women, “We must believe in ourselves or no one else will believe in us; we must match our aspirations with the competence, courage, and determination to succeed, and we must feel a personal responsibility to ease the path for those who come afterward.”

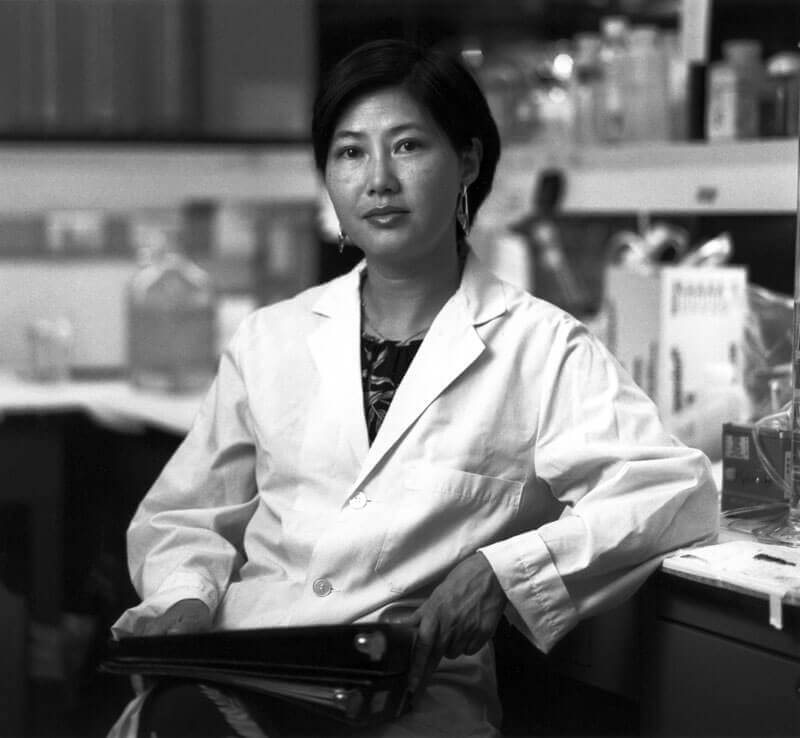

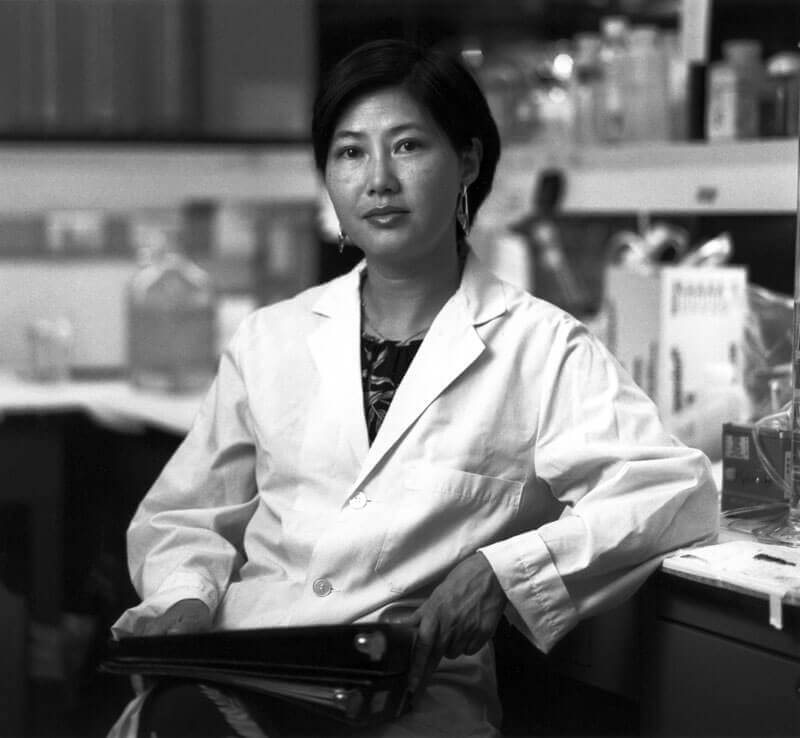

3. Flossie Wong-Staal (b. 1947), Leading HIV and AIDS researcher

- Flossie Wong-Staal at the National Cancer Institute. Photo: National Cancer Institute/Bill Branson

At the age of 18, Flossie Wong-Staal left Hong Kong to pursue her passion for biology in the United States. After completing her PhD in molecular biology

in 1972, Wong-Staal moved to Bethesda, Maryland to study retroviruses with pioneering AIDS researcher Robert Gallo at the National Cancer Institute.

Together they searched for the cause of AIDS, which was by then spreading in the United States. In 1983, Wong-Staal, Gallo and their team discovered

HIV, the virus that causes AIDS.

Two years later, Wong-Staal became the first scientist to clone and produce a genetic map of the virus, both of which were critical steps toward the development

of blood tests for HIV. Wong-Stall continued her research on the HIV virus for over a decade, and today she help leads a biopharmaceutical company

she co-founded which is working to develop improved drugs for Hepatitis C.

Wong-Staal, who is the mother of two daughters, said of her interest in research, “For me, as for most researchers, the main motivation is simply the satisfaction

of making discoveries, finding things out that no one knew before.”

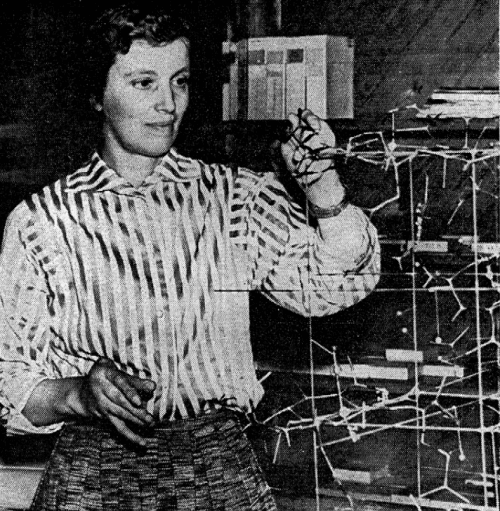

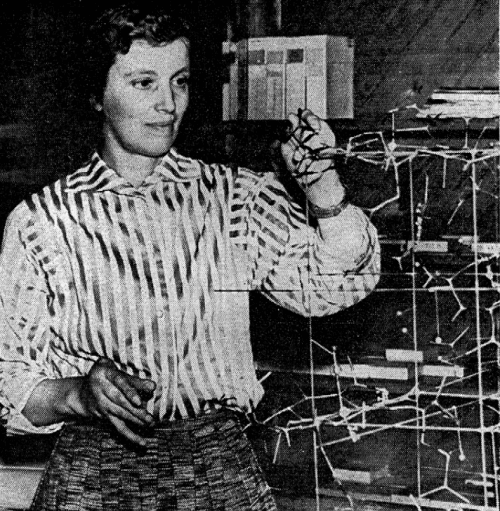

4. Dorothy Hodgkin (1910-1994), Mapped the structure of penicillin

- Dorothy Hodgkin demonstrates the structure of vitamin B12 with a model. Photo: C&EN Archives

Born in the early twentieth century, Dorothy Hodgkin was a trailblazer for women interested in the sciences. As a teenager, Hodgkin received as a birthday

gift from her mother a book by Nobel Prize–winning physicist William Henry Bragg that discussed using X-rays to “see” the three-dimensional structure

of molecules. This present would change the course of her life. Fascinated by the ideas presented in the book, Hodgkin would make the study of this

field her life’s work.

After graduating from college, Hodgkin found a position in an x-ray crystallography lab where she went to work studying the complex organic molecules that

help a living organism function. The technique she used involved crystallizing the substance she was studying, shooting X-rays at it, and then studying

the ways the X-rays refract off the structure in order to determine its shape.

In 1946, after four years of studying the antibiotic penicillin using this technique, Hodgkin determined its structure, marking an important advancement

which would help manufacturers create semisynthetic penicillin. Over the course of her career, Hodgkin also determined the structure of vitamin B12

and insulin. In 1964, she became the third woman to win the Nobel Prize in chemistry.

A mother of three children and grandmother of three grandchildren, Hodgkin said of her career, “I was captured for life by chemistry and crystals.”

5. Margaret Sanger (1879-1966), Birth control pioneer

- Birth control pioneer Margaret Sanger. Photo: public domain

Margaret Sanger devoted her life to expanding the availability of birth control and contraceptive options for women. Sanger’s devotion to this cause was

born out of personal tragedy. At age 19, Sanger watched her mother—who gave birth to 11 children and suffered seven miscarriages—die of

tuberculosis. Sanger believed that her mother’s repeated pregnancies had weakened her body’s ability to fight the disease.

Wishing to build a different life for herself, Sanger became a nurse. Serving the people of New York’s Lower East Side, Sanger tended to the needs of impoverished

women who lacked effective options to prevented unwanted pregnancies and often resorted to back-alley abortions in desperation. This experience deepened

Sanger’s resolve that women needed access to safe and effective contraceptives so they could stay healthy, limit their family size as desired, and

break the cycle of poverty.

As a young mother of three children, Sanger switched her focus from nursing to advocating for the legalization of birth control and making it universally

available to women. Although Sanger experienced several legal victories over the next three decades which expanded contraceptive access, she remained

frustrated by the lack of birth control options available to women and dreamed of a contraceptive pill that would be as easy to take as a vitamin.

To make that dream a reality, she recruited reproductive health researcher Gregory Pincus and raised the needed funding from heiress Katharine McCormick.

This collaboration would lead to the development and introduction of the first oral contraceptive in 1960.

Today Sanger’s vision of a world where all women have the ability to prevent or space their pregnancies remains only partially realized. Although more

than 99 percent of American women have used a contraceptive method in their lifetime,

an estimated 222 million women in developing countries want to limit or control the timing of their pregnancies but lack access to modern contraceptives. Said Sanger, “No woman can call herself free until she can choose consciously whether she will or will not be a mother.”