In this guest post, Dr. Monica Parise—deputy director for program and science—and Dr. Larry Slutsker—director of the Division of Parasitic Disease and Malaria—at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Center for Global Health—discuss the role of research in advancing efforts to detect, prevent, and eliminate parasitic diseases.

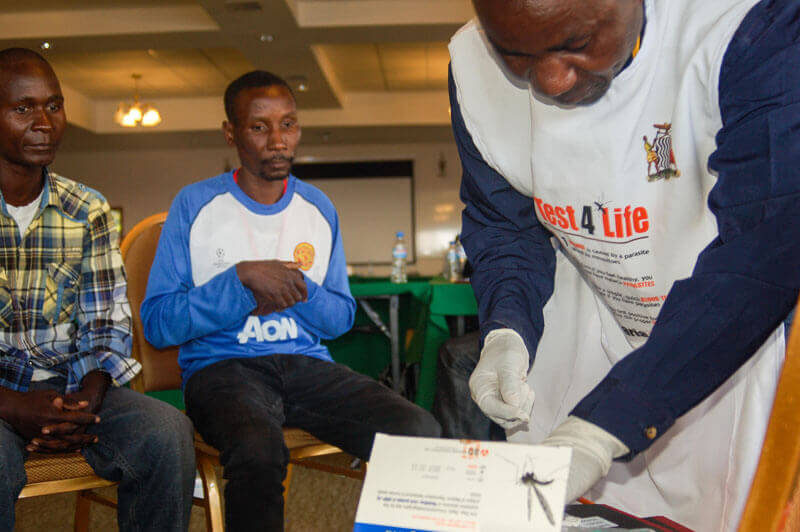

- Research is critical to preventing, detecting, and eliminating parasitic diseases. Photo: PATH/Gabe Bienczycki

It’s an inspiring time for those of us working on parasitic diseases. Combined, the two of us have spent several decades working to address these infectious

diseases that are major causes of death, disability, and suffering for millions of people. Since 2000, we’ve witnessed tremendous successes in reducing

the devastating toll from malaria and several of the neglected tropical diseases (NTDs).

None of this happened by accident. Sustained commitment from global partners, combined with unrelenting work and attention, has produced results. Massive

scale-up of malaria interventions has saved more than 4.2 million lives since 2000, and globally, child deaths have fallen by 47 percent and in sub-Saharan

Africa, by 54 percent. There has been similarly impressive progress in eliminating lymphatic filariasis, also known as elephantiasis, with an estimated

97 million cases prevented. We have also seen massive reductions in cases of Guinea worm disease, with only 126 cases from the four remaining endemic

countries reported globally in 2014 compared to 3.5 million in 1986.

Based on these gains, several NTDs, including lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, and trachoma, have been slated for elimination within the next five

years. Equally significant, the newly released Global Technical Strategy for Malaria calls for eliminating malaria in at least 35 new countries by 2030.

But this progress is fragile. This is no time to be complacent.

While the documented and real successes should be applauded, they’ve also produced a changing epidemiological landscape that has altered such things as

the infection levels, where transmission still occurs, and other factors. Increasing resistance of parasites to drugs and mosquitoes to insecticides

threatens to unravel progress in malaria elimination. NTD elimination programs are reaching a point where they now require better and different tools

for making decisions about when to stop mass drug administration and how best to monitor for disease reoccurrence.

To succeed we must adapt so that we keep pace with rapid changes in our foes—the parasites and their vectors. We must identify new tools and approaches

to continue to achieve gains.

That requires introspection and the willingness to occasionally stop and ask hard but essential questions. As scientists, as well as public health professionals,

we constantly ask ourselves: Do we as a community have what it takes to get to the end? Do we have the information, tools, and interventions needed to successfully support a path to elimination? If not, what do we need to do about it?

Over the past several months, the two of us, along with colleagues in CDC’s Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria, reflected on these challenges and

considered possible solutions. The result is a set of strategic priorities to guide our work over the next five years. An important area of focus is research to develop new tools and approaches—to further drive down

transmission, overcome technical challenges, and measure progress. We identified specific gaps that need to be addressed:

- Strengthening the evidence base to support elimination of malaria and NTDs: Additional guidance is needed to help define when a program

should stop mass drug administration and transition from control to elimination strategies. Guidelines are also needed to identify which interventions

are most appropriate in low transmission settings.

- Developing and evaluating tools and interventions targeting both the malaria parasite and its mosquito vector: Drug and insecticide

resistance are forcing us to think about novel ways to battle those long-time foes, including evaluation of promising vaccines and novel vector

control strategies such as spatial repellents—airborne chemicals that prevent human-vector contact with given space—and insecticide-treated

durable wall linings.

-

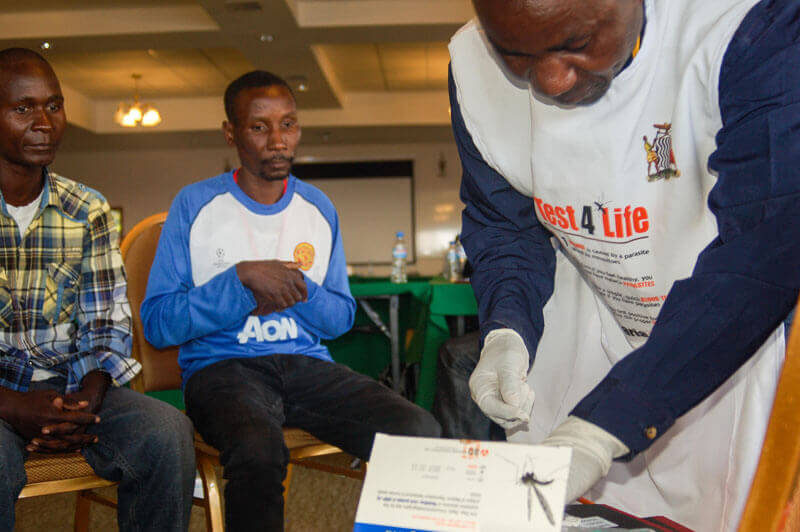

- Malaria screening undertaken by community health workers. Photo: PATH/Lynn Heinisch

Developing interventions to improve management of malaria cases: Achieving further reductions in malaria burden will require moving

diagnosis, treatment, and risk mapping beyond the health facilities and community health workers providing clinical care, to developing strategies

for population-based approaches such as focused screening and treatment, mass screening and treatment, and mass drug administration.

- Optimizing the effectiveness and mix of interventions: Whether it is a promising vaccine or a new method of vector control, no single

intervention is likely to be a “magic bullet” for malaria control and elimination. Adding new tools and interventions into the mix of ones currently

in use will require an understanding of which tools—used when and how—are needed.

- Evaluating the impact of parasitic disease control programs on other endemic diseases: Because individuals are commonly infected with

more than one parasite or other disease-causing organism, opportunities and efficiencies exist for integrating interventions. Evaluating how parasitic

disease control programs impact other endemic diseases can provide additional information on how to maximize resources and further integrate programs.

- Improving global research capacity for parasitic disease prevention and control through technical assistance and training: Ultimately,

the goal is for governments and their academic partners in endemic countries to develop the capacity to lead research efforts to advance disease

control and elimination within their own setting. The advancement of parasitic disease research is dependent upon strong research collaborations

both with ministries of health and their partners in endemic countries and here in the United States. While adequate research infrastructure exists

in some areas, there is a need to strengthen capacity through technical assistance and training that will facilitate collaborative research.

We should celebrate the successes of the work so far that has saved millions of lives and eased suffering worldwide. But there is more—much more—to

do. We must continue to scale-up existing technologies to sustain progress while at the same time advancing scientific research that will inform the

way forward. With a strong base in science to support effective programs and policies, we are in a far stronger position to meet the challenges we

face on the path towards elimination.