Tom HarmonInternational AIDS Vaccine Initiative

Tom Harmon is a Senior Policy Analyst at the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, a nonprofit working to develop preventative AIDS vaccines that are safe, effective, and accessible to all people.

In this guest post Tom Harmon, senior policy analyst at the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI), highlights a new analysis exploring the critical role of a vaccine in ending AIDS.

When we talk about ending AIDS, what do we mean?

The last dozen years have brought tremendous strides in reducing new HIV infections in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), expanding lifesaving treatment to almost 16 million people living with HIV, and implementing programs to address the epidemic in populations at especially high risk, including women and girls. But we must continue to push for progress in treatment and prevention. The 2 million new infections in 2014 remain far too high, and almost 60 percent of people needing treatment are not getting it.

So, when we talk about conclusively and durably ending AIDS and ensuring that it does not bounce back, our experience with other infectious diseases shows that a preventive vaccine will be necessary.

The global effort to develop an AIDS vaccine has also recently experienced significant successes and steps forward. For example, we’ve never before seen such a diversity of approaches and partners, with follow-on trials based on the first candidate to show modest efficacy slated to begin later this year in South Africa, exciting new insights toward generating protective antibodies against HIV, and promising approaches toward inducing cellular immune responses that could control HIV infection.

Still, there are more far-reaching questions we’re asked today by policymakers, advocates, communities, and even researchers themselves: What would the global response look like if an AIDS vaccine was available? How effective would it need to be? Would it be cost-effective and affordable?

A new article, published in PLoS ONE aims to answer some of these crucial questions. The result of a collaboration between IAVI, Avenir Health, and AVAC that builds on work by UNAIDS, this model specifically explores a vaccine’s potential value in terms of preventing HIV infections in LMICs.

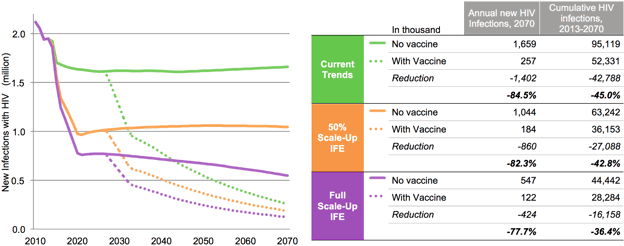

We analyzed a vaccine’s potential impact depending on how well the world can achieve ambitious HIV and AIDS program objectives, how effectively it can prevent HIV infection, and how it can add to a response that also includes pre-exposure prophylaxis and treatment as prevention. We also looked at cost scenarios to see how a vaccine would stand up to cost-effectiveness criteria used by the World Health Organization to guide the introduction of new health technologies.

Despite the potential for today’s tools to have a substantial impact on the epidemic, our results show that a vaccine is a critical piece to ending AIDS. Under our base scenario, a vaccine of 70 percent efficacy with strong uptake would reduce HIV infections in LMICs by 44 percent in its first 10 years and by 65 percent in 25 years, ultimately averting tens of millions of infections and saving millions of lives.

A vaccine would be impactful and cost-effective even at lower efficacy levels and costs far higher than many of today’s vaccines. Increasing a vaccine’s efficacy, ensuring it protects for a longer period of time, reducing the number of doses, lowering the cost of a dose, and more effectively rolling it out are all factors that would increase a vaccine’s impact and its value. Such a vaccine could cut the number of people needing treatment in half by the year 2070, and eventually reduce the total cost of fighting AIDS in LMICs even when the additional cost of implementing the vaccination program is included.

While these data provide a powerful illustration of a vaccine’s potential value, we acknowledge and welcome discussions of its intrinsic limitations, which reflect the areas the AIDS vaccine field and future program implementers will need to tackle as we research, develop, and ultimately deliver a vaccine to the people who need it most.

Such an analysis helps explore the parameters that determine the medical and economic impact and value of a future AIDS vaccine as part of the comprehensive HIV and AIDS response. This data can be a useful guide for research portfolio decisions as new candidates move closer to efficacy trials. In many ways these projections are as much a vaccine development and delivery “to-do list” as they are a crystal ball for what the future holds.

A few weeks ago, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention organized a Grand Rounds presentation on how models are used to guide pandemic responses. This interesting panel was closed by Dr. Richard Hatchett, chief medical officer and deputy director for strategic sciences at the US Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, who cited modeler Steven Bankes’ use of campfires as an analogy for predictive models, in that their value goes beyond their primary deliverable (be it light, heat, or data), as they just as importantly provide a “gathering place” for discussion between stakeholders.

Our new model can perform just such a dual function, adding valuable context for a vaccine’s future role in ending the AIDS epidemic which has ravaged so many communities, while stimulating conversations and new questions on what we need to do in the real world to turn theory to impact.